Music, besides a purely sensual, and often surreal, kind of enjoyment, has a million facets and presents a wide array of different challenges for different mentalities: for performers, music is a fluid oscillation between obtaining eloquent delivery of tones and phrases, and reimagining the philosophical pillars with which the piece in question was derived; for composers, and usually scholars as well, music yields a metaphysical reality, by pursuing which our concerns about material, and sometimes even practical, realities shrivel; for the general audience (assuming one that is familiar with the context of the piece they listen or recollect), music tends to be interpreted as a manifestation of an all-encompassing, higher being, in which the listener is dissolved, elevated to a vantage point, and able to re-deliver the comprehensivity of the music.

Discussions of the psychological impact of music are often imbued with that praising its extraordinary illusionary capabilities. This observation, however, pertains directly to an integral part in musical imagination: space. Composers use techniques of distance and spatiality to create a premise for intricate structural progressions and volatile ideas; sometimes it becomes so compelling that the listener’s awareness of the surrounding is completely subsumed into it. In such cases an ‘environment’ is created. In relation to more traditional aesthetics, the sole agenda of creating space is to create an alternative path towards metaphysical reality, apart from teachings of reasoning. Space instills fertility of thought in us. When we listen to music attentively enough, the boundary between the listener, who perceives sonic information, and the music, which configures and ‘emanates’ the information, is obscured; therefore it is not hard to imagine the multiplicity and simultaneity of perceptual conduits and the listener’s self-awareness achieved by spatialization, through which the attentive locating of sound — sometimes the listener’s subconscious, self-seeking appreciation of such attentiveness as well — is transposed to a kind of panoramic ‘vision’ when the listener recognizes another sound source. The experience is then translated into, to a certain extent, an experience of anonymity and metaphysical clarity beyond the subjectively imposed characterization of external sonic objects. Ultimately, a virtual environment is created, and the listener is rendered receptive of it; the processes of signification is diluted within a complex procedure of transitioning between being and non-being. The listener’s ideas are therefore, ideally, equally represented and given ‘amorphous’ shapes according to how the composite matters are delimited and when the ideas ‘intersect’ the music during the listening experience. When we internalize spatiality, polyphony begins.

The spatialization technology has nowadays been primarily associated with electronic settings thanks to the proliferation of electronic music and development of electronic equipments. Its root, however, can be traced far back to the antiphonal singing of chants in the medieval era. The antiphonal style, that is, the call-and-response setting between segregated choruses, has been implemented in chants more than the responsorial (solo-chorus) style and the direct (unison choir) style. Besides exploring the poetic images behind the antiphons, the Renaissance era inherited the performance practices and further intensified implicit soundscapes in significantly elaborate polyphony. One can relate this movement to concurrent scientific discoveries (or, perhaps more accurately, the acknowledgment of their validity from the Church) regarding the motional and spatial relativity between Earth and other celestial objects, which helped replacing the Earth-centric view of the universe with a spatially much greater one. The explosive expansion of the hypothetical universe led to a new way of looking at space; the spherical representation of the universe and the sphere as a theological representation of perfection both emerged during this period, and the octave, considered the most ‘spherical’ of all intervals, was employed in ways of enhancing, regulating and reorganizing the tonal space — the handling of tonal implications and motional relativity had been increasingly reified and conceptualized such that it virtually became a ‘spatial’ parameter — which correlates to a revised end-goal of contrapuntal writing. Counterpoint had been treated as, obviously enough, a rigorously linear, ‘contrapuntal’ context in the previous century. This can be seen in Johannes Tinctoris’ formulation in his 1477 thesis Liber de arte contrapuncti:

Counterpoint is a regulated and rational concentus [literally, “singing together”] realized by setting one voice against another. Its name counterpoint derives from counter and point, because one note is set against another as if it were constituted by one point against another.

Tinctoris , Liber de arte contrapuncti, 1477

However, new ideas emerged unhindered, and we see the recognition of the totality of polyphony as a ‘body,’ an organic whole. Counterpoint had since therefore been endowed a mystical quality. Here is one example of numerous expressions of the then-revolutionary theory, quoted from Franchinus Gaffurius’ Angelicum ac divinum opus musice, written in 1518:

The concento or many-voiced work is a certain organism that contains different parts adapted for singing and disposed between voices distanced in commensurable intervals. This is what the singers call counterpoint.

Gaffurius, Angelicum ac divinum opus musice, 1518

The latter one, notably favored by theorist Gioseffo Zarlino who appropriated the quote nearly verbatim in his seminal treatise Istitutioni harmoniche, combined the perception of external spatiality and that of the internal analogue into a single, transcendent unit. If external spatial distribution was to be viewed as insufficient to fulfill our perceptual intuitions, Gaffurius’ conception of the organic composition may well serve to alleviate the apparent mediocrity of the seemingly signal-like, ‘unmusical’ tactics. In other words, spatialization had again been able to yield its perceptual potency thanks to the intensification of tonal organization. Further discussion of its aesthetic history can be found in this beautifully written paper.

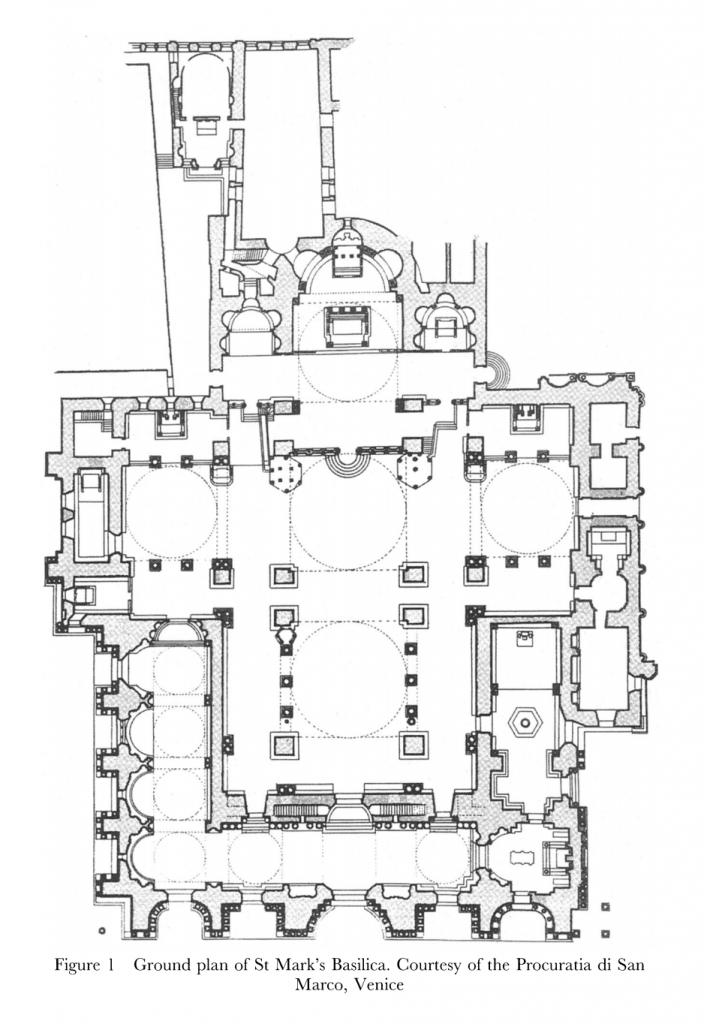

The revitalized interest in spatial arrangement was evident in the architectural plans of Catholic churches. Many of the them have places specially designed for antiphonal choirs; in this article, the author specifically examines the floor plan of St Mark’s Basilica in Venice.

The liturgical significance of antiphonal settings is evident here; while the organ is introduced into architectures, spaces are retained for antiphonal choirs.

Unsurprisingly, antiphonal writing is enormously difficult because, by the time polyphony came into fruition during the mid- and late-Renaissance era, segregated choirs were treated not only as purely antiphonal but also as a composite choir. Besides maintaining independence of melodic lines, the composer has to manage the composite choir — typically an eight-part force divided into two four-part choirs with equal forces — in a way that the independence of individual choirs can be recognized while the unity of the eight-part body is preserved. In Istitutioni harmoniche Zarlino wrote about the principles of writing of this kind:

Because the choirs are located at some distance from one another, the composer must see to it that each chorus has music that is consonant, that is without dissonance among its parts, and that each has a self-sufficient four-part harmony. Yet when the choirs sound together, their parts must make good harmony without dissonances. Thus composed, each choir has independent music which could be sung separately without offending the ear.

Zarlino, Istitutioni harmoniche, 1558

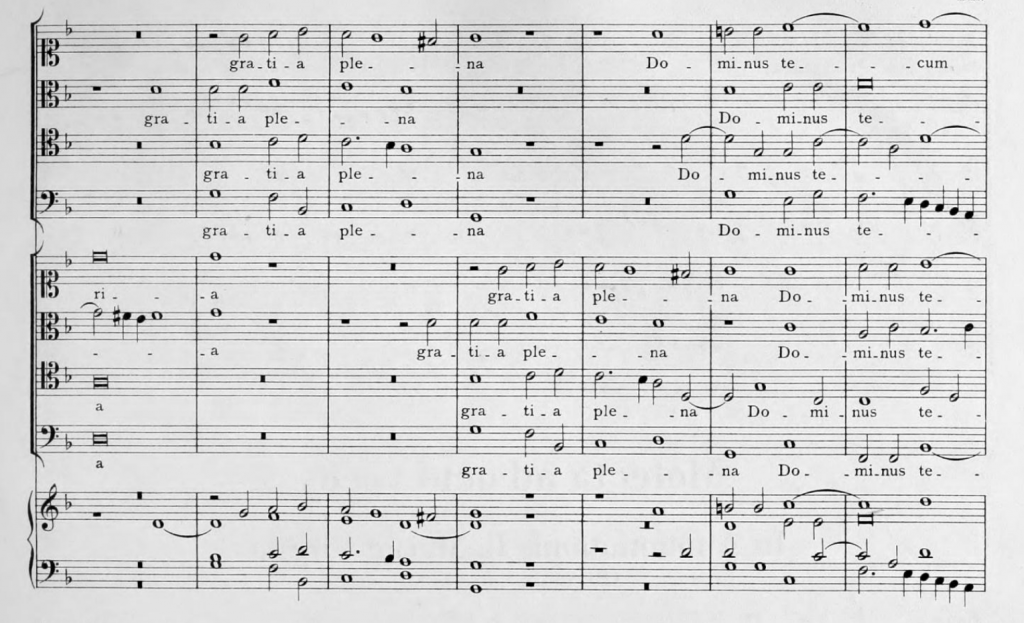

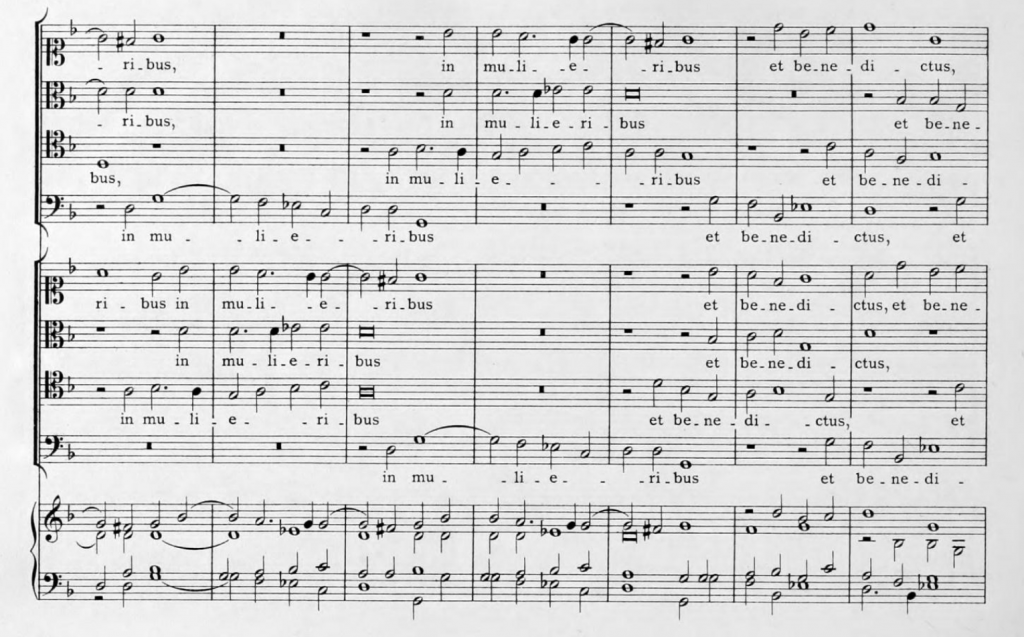

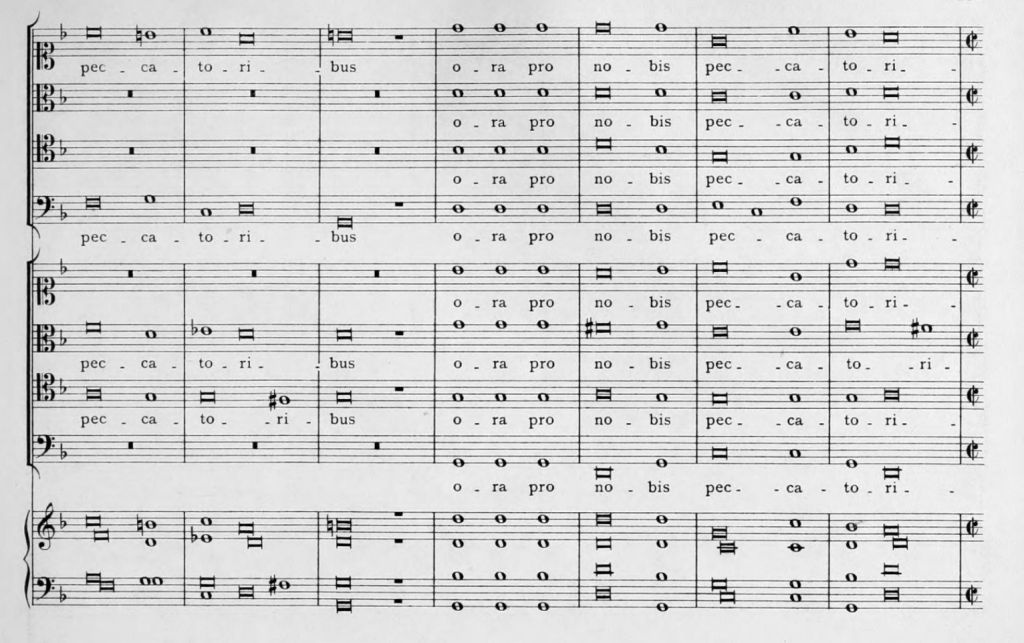

One example of eight-voice setting is the Ave Maria (1572) by Tomás Luis de Victoria, included in the supreme compilation of his musical art Missae, Magnificat, Motecta, Psalmi, published in 1600. This motet incredibly encapsulates different kinds of choral writing, all fused in a compelling dramatic trajectory. In addition to eloquent shifting between kind to kind, Victoria exploited the organizational possibilities within the expanded setting, usually when the texture is diminished into four parts. The curtailed choir, however, may be drawn from both sides of the entire force as opposed to one; the strict, ‘primitive’ distinction of sides which once defined antiphony became a form of interlacing, its original functional implications — to elicit call-and-response reciprocations — giving way to intricate transitioning between different pairs of different distances. To carefully calculate the relative amplitude of each side is to manipulate the ‘movement’ of a sound (not to be confused with that of a pitch, which is contour) — an implicit, heavily context-dependent, yet immensely affective parameter.

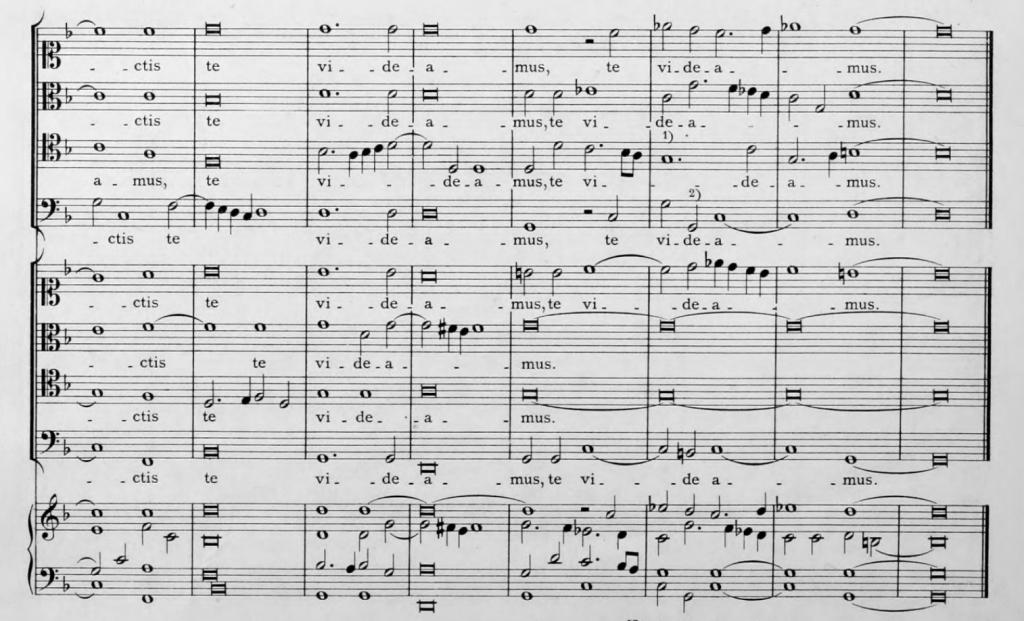

Victoria, Ave Maria, mm. 8 – 14. Antiphonal exchange transitions into florent, eight-voice polyphony. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel, 1902.

Victoria, Ave Maria, mm. 22 – 28. Non-segregational groupings of four voices, occasionally coalescing into five- or six-voice sonorities. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel, 1902.

Victoria, Ave Maria, mm. 65 – 71. Choir sings in rhythmic unison, reminiscent to the ‘direct’ style of medieval chants. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel, 1902.

Victoria, Ave Maria, mm. 86 – 93. Florent, eight-voice polyphony in the concluding measures. Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel, 1902.

For further investigation of the performative considerations of an eight-voice setting, this article offers a detailed discussion of Victoria’s Victimae paschali laudes, a sequence also included in the 1600 collection Missae, Magnificat, Motecta, Psalmi.

The spatial component saw a second rise in significance in the nineteenth century and a full fruition in subsequent centuries. In the third movement of Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique, an oboist is instructed to remain offstage while playing the remote echoes of the shepherd’s melody, which is in turn played by the english horn; the schalldeckel in Richard Wagner’s revolutionary Bayreuth Festspielhaus reflects the lush orchestral sound from the pit back to the auditorium in a way that at any given point the sound seems to be completely immersive and all-directional; Luigi Nono credited the Venetian masters in the Renaissance era as of primary importance in his music because spatialization directly pertains to contemporary theatrical philosophy. Such is the relevance of our instinctive awareness of surroundings to metaphysical and spiritual truthfulness. However, spatialization through purely contrapuntal means is no less complex than the handling of the electronic facilities. Perhaps, evocation of a primal revelation and reverence — although it may appear more akin to an ‘unlearning’ process — could only be plausible through our rigorously regulating, reinventing and augmenting the conduit for an authentic yet universal experience.

— I-Hsiang Chao

Your consideration of space as a music technology is really interesting! I think once performance spaces are done being built, performers take for granted how intentionally they were designed in terms of acoustics/spatial features (even though composers definitely don’t), so seeing space through the lens of technology is really cool. The article about Architectural Spaces for Music and specifically the floor plan of St Mark’s Basilica was illuminating and really effectively put your argument of space as technology into context. It may have been helpful if you described a couple of specific spatial features that made this layout ideal for antiphony right in your post in addition to linking to the article. In terms of your writing, I think you did a great job of fitting a lot of information into a relatively compact space, but I think you could maybe use shorter sentences at times to make your points more separate and easier to follow. Overall this was a fantastic, informative post! Great job!