Technological development is tied with the concept of perfection—people believed that, through inventions and discoveries, they were able to do things that needed to be done. Every new creation of technology is supposed to be perfect, because it serves specific purposes and follows a set of rules. At least that’s what people expected from it: purposiveness, meaningfulness, and perfection.

However, everything started to change while we step into the digital age, or, as some call it, the information age. The manipulative power of the Internet and the rise of consumer technologies create an unprecedented environment. As one receives vast information and acknowledges infinite technological possibilities, it becomes impossible for one to really harness them. We lose control of basically everything, because our choices are deeply influenced by the behaviors of technologies themselves; if, at first, it was human who decided what technology should do for us, it now seems that the technology is telling us what human should do. This exchanging of the two sides leads to disillusionment: both the purpose of technology and the identity of human are lost, and people have long criticized many aspects in this situation.

But what if this “perfect” technology intentionally make mistakes? What if we no longer strive for improvement of its functionality? As a response to the existential problems provoked by the digital age, some artists propose new ways of looking at technology, and the one we are focusing on in this blogpost is called “glitch aesthetics”.

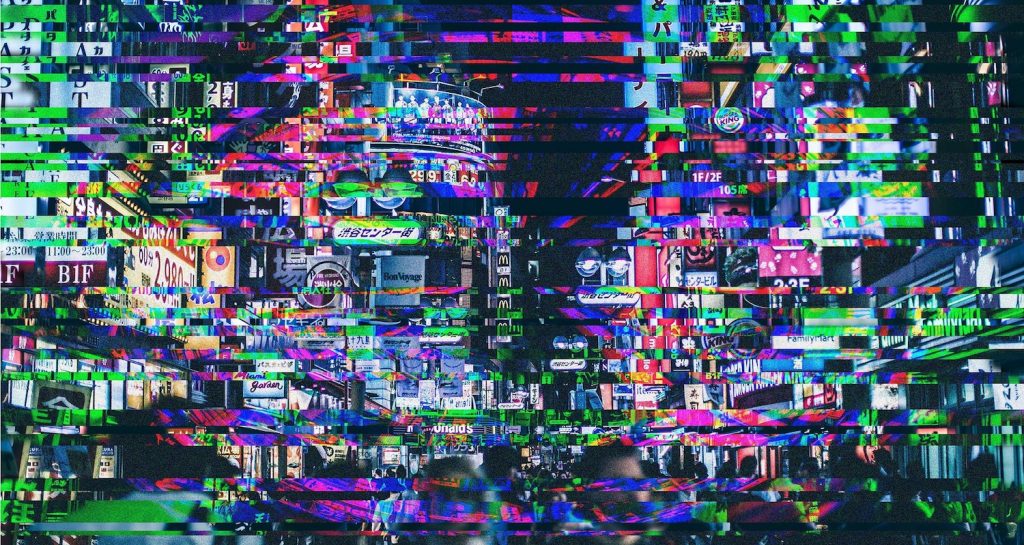

Glitches are not stranger to our technological environment. In fact, we encounter them everyday: turbulence of television signals, malfunctioning software, and instability of internet connection…all have immediate influence on our user experience, and a glitch refers to a visual or physical manifestation of an error. During a glitch, the system fails to carry out its tasks, and the failure is directly shown in ways such as flickers on a screen, an error message in the operational interface, or the skipping of a defective CD in the CD player. Art works that deal with glitch aesthetics would intentionally expose or produce these manifestations of errors in technology, and what they attempt to present through such methods, according to the art organization “GLI.TC/H”, is the exact moment of the technological failure which gives a window into the technology’s abstract system, into the internal processes of its function. For example, in the moment of a display error, the RGB lights on the screen dance in frenzy, showing its most basic constituents. These mistakes were supposed to be “imperfections”, and were to be avoided in order to let the technology function correctly; yet artists have created works that appropriate these “imperfections”.

It is interesting for me to see artists presenting the imperfection of technology, because it provokes a sense of “Frankensteinian” nostalgia: as the technology refuses to reach its original goals, it almost seems that it is having its revenge on people’s manipulation, and the thought that technology is claiming its own identities in turn calls to people, reminding them to find their authentic “selves” as well.

What will happen then, if one brings all these defects of machines back to the human body? A particular work serves especially well as an example of this concept.

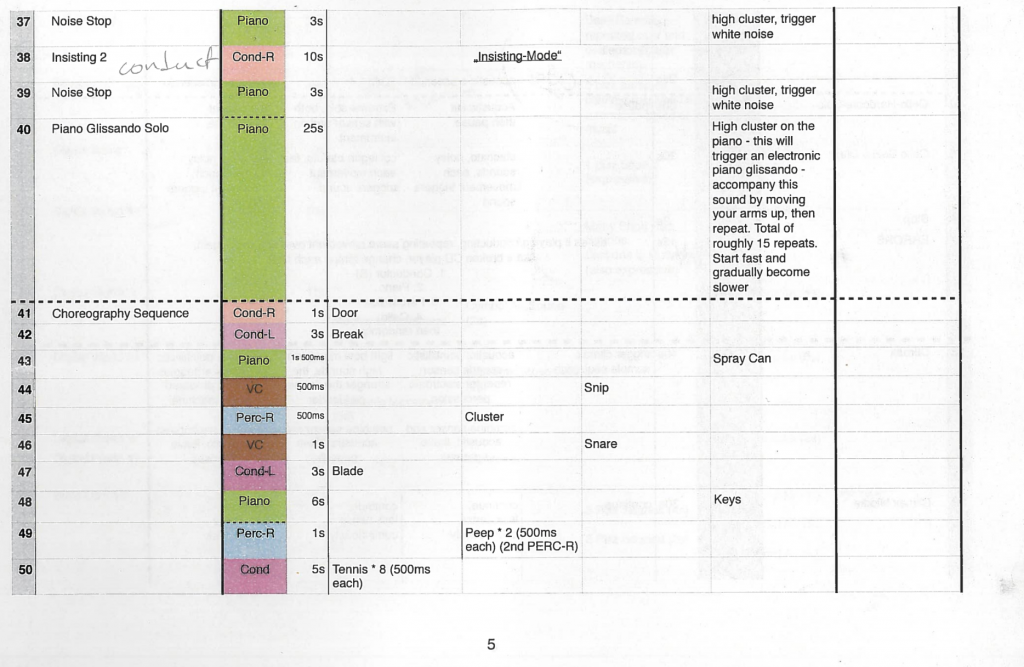

The score for Alexander Schubert’s “Serious Smile”, a piece written for three instrumentalists, a conductor, and live electronics, is notated completely by aleatoric methods. Word instructions tell the performers what kind of things they should do, for example, “play some high clusters” is the only thing given to the pianist in the score at times. This means that specificity of pitches is not needed for the performance of this piece, but rather other aspects which I will discuss now.

One of the most significant aspects of this piece is that it uses motion sensors to enable the performers, including the conductor, to control the sound of the electronic part, so that their physical movements trigger series of prerecorded or synthesized sounds. Many of these sounds clearly refer to malfunctioning electronic devices, collisions of metallic and plastic machine parts, and low-quality midi sound sources. Because the velocity and frequency of the occurrences of these sounds are at times directly controlled by the gestures of the performers, the piece gives the audience an illusion that as if the performers are a group of malfunctioning robots; yet, knowing that the performers are actually human, the piece expresses an unresolvable paradox, a duality of flesh and artificial parts. However, one is absolutely not able to receive this message if one only listens to the audio recording of the piece, and this is where the vital component of the piece—the visual/choreographic elements—plays its role.

The score for “Serious Smile” focuses rather strongly on the ways that performers move on stage. Instructions at the beginning says that “the piece is as much a choreography as a musical piece”, and that the performers should be fully aware of their appearances on stage. Additionally, the performers are told to maintain the quality of inhumanness throughout the piece: movements should be as robotic as possible; specifically, performers should show the differences between a human and a machine through the unnatural and clumsy manner of waving their arms, playing their instruments, etc.

One of the repeated passages in this piece is called “frenzy” in the score. Performers play their instruments (or conduct, for the conductor) or move their bodies (while triggering all kinds of “error” sounds using their sensors) in a continually convulsive manner, resembling the glitches on electronic screens caused by display errors. Sudden long pauses of their movements, then, represents “freeze glitches”, indicating a loss of signals. The sound at these points, which is violent noises that happen when network connections of devices are lost, is also very important in producing this human embodiment of frozen display. Another very impressive moment for me is the passage where all the performers imitate certain human behaviors that are constantly disturbed and corrupted by each others, which resembles the effect of the mentioned skipping CD player; Alexander Schubert intentionally plays with the duality of flesh and machine, stressing the jarring incompatibility of human and robot.

Another aspect which I consider essential to the overall effect of the piece, which was actually added by the producer of the video above—Ensemble Intercontemporain—rather than the composer himself, is the manipulation of lighting. Rapidly flashing lights enter when “frenzy” passages begin, and that changes everything: it is no longer only the players that embody the glitches, but the whole stage; now that the stage corresponds with the performers’ movements, it creates a “cyborg world”—an environment even further removed from the audience, yet, with this unique effect of magical(/cyborg) realism, one can make deeper connections with the performing “robots” and oneself. When it comes to video editing, Ensemble Intercontemporain is then free to use all kinds of close-ups to show the performers’ movements more clearly, because the lighting already indicates the interactions between the players, and not too many distant views of the ensemble are needed.

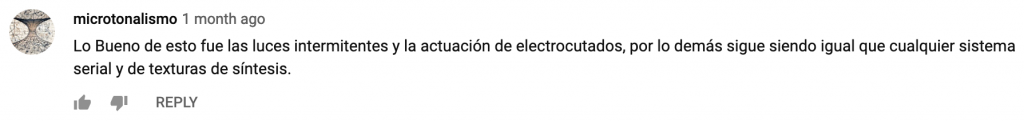

Audience has evidently realized that all the striking aspects of the piece cannot be achieved without the help of visual/choreographic design. One audience comments that the only good thing about the piece remains in “the flashing lights and the performance of the electrocuted”, otherwise the sonic aspect of the piece is generic and uninteresting, resembling other typical serial and synthesis music. Another says that the electronic part is interesting, but the acoustic playing is just appropriating pieces by Xenakis.

From these criticisms one can see that “Serious Smile” challenges the concept of music itself. In correspondence with the question of “what a machine or a human can be”, new conceptualist composers like Alexander Schubert propose the question of “what music can be”. Both questions touch the core of the digital-age contemplation, a constant denial and doubt of meanings in the era of loss of directions.

The glitch aesthetics in “Serious Smile”, therefore, is presented by a collaboration of both the visual and the sonic effects in order to express the dissonance between human and technology. While the performers “enjoy” this dissonance in the state of “euphoria and frenzy”, we as audience are violated, and the piece leaves us with questioning of our own beings.

It is then certainly surprising to see that one audience comments on the video, saying that the performance is “like a Mahler symphony”. What type of “Mahler symphony” is “Serious Smile”? I cannot find the answer. However, what I am certain is that, the visual and sonic elements in the piece speak to us in different ways. Regardless of how clear a concept is presented in a piece like this, the audience can always interpret this presentation in unpredictably varying ways, and that is what I find fascinating about new conceptualist works: composers play with concepts and illusions, and cross the boundaries of art genre and medium, not in order to set new metaphysical rules, but to open a brand new world of possibilities while revealing the internal processes of our thinking, just like a glitch—an abnormal “play” of error that shows the “blood and veins” inside.