It seems that western classical music performers’ pursuits in instrumental sound has always been bit of a paradox. On the one hand, one seeks for an “impossible perfection” of the timbre: players try to work against the physical limitations of the instrument in order to attain flawless sound. No matter how “natural” and “relaxed” one is taught to be, producing a purer sound is always the more important task, and that often results in greater sufferings of the body. On the other hand, many musicians seem to value some occurrences of “imperfection” in music playing. A brief moment of scratch tone, a slipped-aside pitch, or maybe just some unexpected errors of rhythms, can sometimes become the most expressive moment in a performance. Very often, one would even intentionally “distort” the sound, so that a more dramatic effect could be achieved.

But why would that be? What makes a sound expressive? Composers in the 20th Century are intrigued by the reasoning behind these ideas, and they have proposed numerous theories on how the most minute details of a sound changes everything in a performance.

During his lecture on electronic music in 1972, Karlheinz Stockhausen proposed the idea that compressing and stretching the duration of a sound would completely change the listener’s perception of it. Every piece of music can be a distinct timbre, and every brief sound can be a piece of music. This theory regards all sounds as highly complex compounds of information and structure, hence expectedly resonates with the idea that a single molecule is loaded with infinite contents. Indeed, the nature never ceases to overwhelm us with its sheer amount of details, and it is from different combinations of these details can we recognize an object’s quality. If one regards a sound as an object in the auditory realm, one can see what the sound consists of through deconstruction.

However, how does one utilize this idea in music composition? How can one find directions within the vast ocean of sounds which in reality last a single second? The answers are infinite. The micro-structure of a sound is a world of its own, we can of course explore as much as we want in it just the same as in our universe. Here is an example of complex sonic details created by new ways of using materials in a performance.

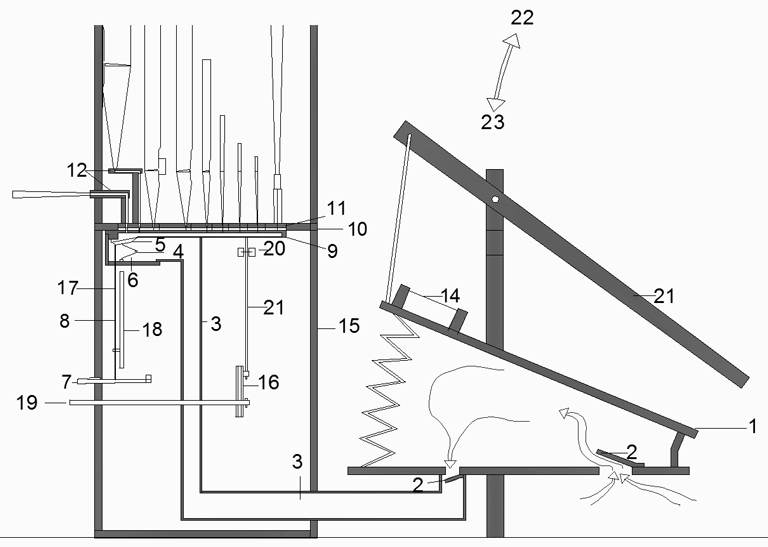

Australian composer Liza Lim uses a unique kind of bow in her cello solo piece Invisibility. The hair is wrapped around the stick of the bow; and, in Liza Lim’s words, “the stop/start structure of the serrated bow adds an uneven granular layer of articulation over every sound.” In her mind, this special bow enables the sound to outline the movement of the player, simultaneously outputting the “grains” and the “fluid”, thus providing new expressive possibilities in the relationship between the instrument and the player. Arguably, it is the instability and randomness in such grains that evokes the sense of body movement.

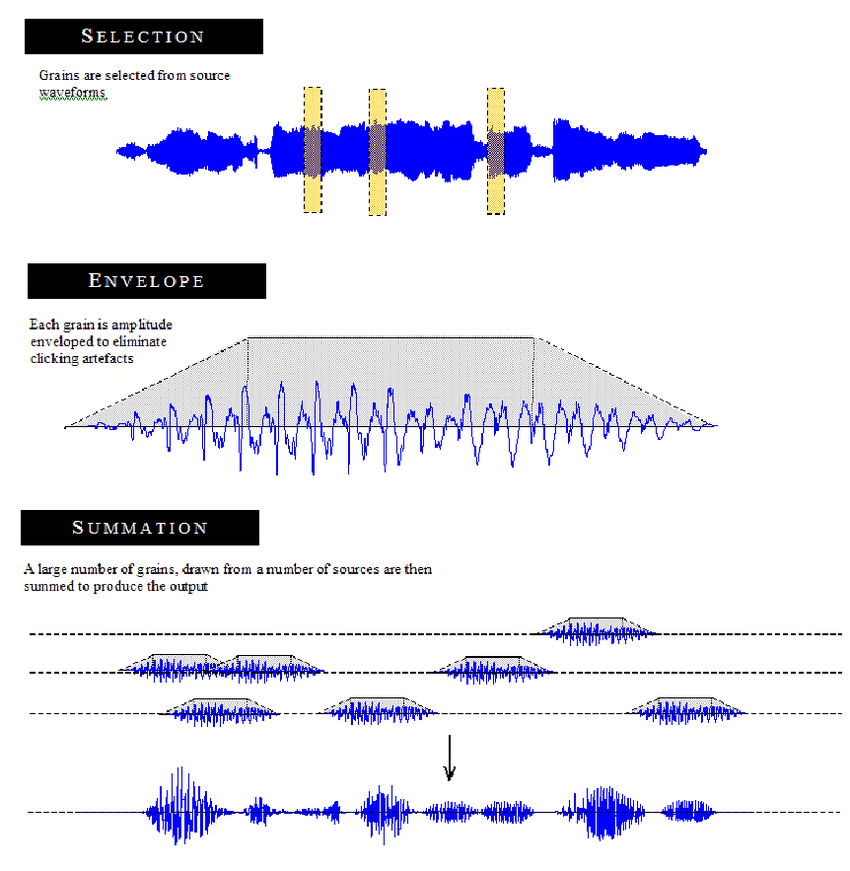

Helped by development of a new type of technology—granular synthesis—in the 20th century, composers were able to find the grains of sound for the first time, and that created a whole world of sonic expression completely unheard before. Arguably, many composers’ use of grain layer in the sound stems from the aesthetics inspired by this new found sonic granulation technique.

The basic concept of granular synthesis is to create a special playback system which splits a sound sample into hundreds of thousands of small “grains”, providing the possibility of microscopic manipulations such as stretching and transposing. Greek-French composer Iannis Xenakis was the first to introduce the use of this concept in musical composition. In his piece Analogique A-B, he physically cuts the tape recordings into extremely small segments and rearranges them when sticking together. It was a tremendous amount of work without the help of computer, and the experiment one could operate is very limited.

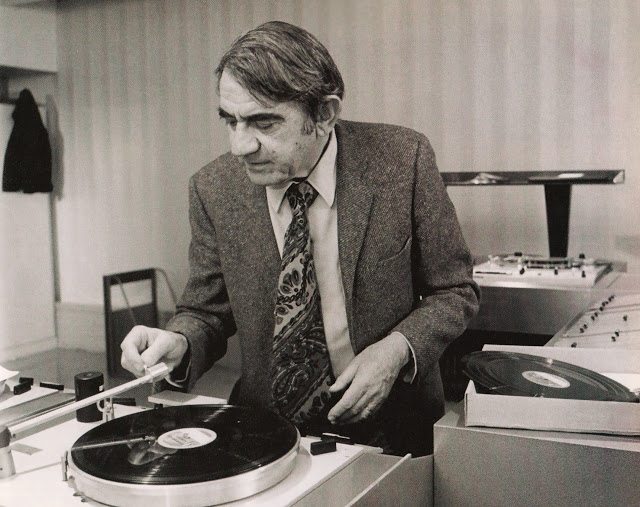

It was not until 1990 when Canadian composer Barry Truax fully implemented the real-time processing of granular synthesis in his piece Riverrun, where he applied a computer program that allows immediate playback in the middle of a sample when changing the configurations of the synthesis. Now one can experiment very efficiently with all kinds of granulations of sound, and in real-time transition from one kind to another gradually in order to create difference in fluctuation as a musical parameter. With this advanced granulation system, one can truly combine the mentioned ideas proposed by Stockhausen and Lim: the sense of physical movement achieved by stretching and exposing the details of sound, that is the sonic particles, the complexity of grains. Below is a piece called “Bamboo, Silk and Stone” by Truax for Koto and electronics.

In the piece, the player performs the initial material for granulation, and the tape would then answer it with the granulated sound, and so on so forth. Source materials from bells alike are also added in the piece, along with the granulation of those sounds. From the processed sound of the electronics, we can see that Truax uses granulation to segregate each attack from the Koto sound, making it into a fast group of identical “clouds” of sound that has a ghostly quality. We can also hear airy sound with rapid pulses which derives from sound of the vessel flute Xun. Such transformation produces the effect that as if the sound is physically constructing and deconstructing itself. The reason one might have such impression is that, in the process of stretching and magnifying the small grains of sound, the characteristics of that sound is still perceivable. Therefore, we can say that, through microscopic manipulations, we can treat sounds fully as physical objects and make them flexible to distortion without losing their own identities.

Working with the vast details and finding the physicality in sound has not only given birth to new forms of electronic music and compositional inspirations, but also provided new insights into performance practices.

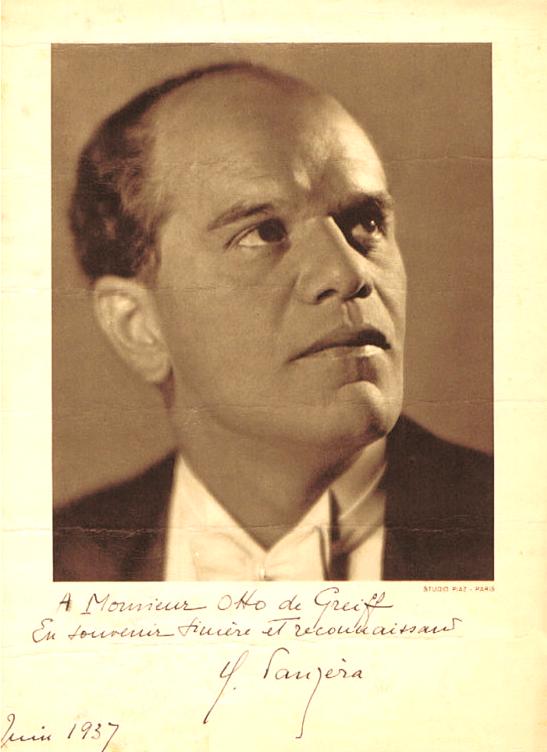

In his essay “The Grain of the Voice”, French philosopher Roland Barthes examines and compares the quality of two singers’ voices (Panzera and Fischer-Dieskau) and explains why he finds one of them (Panzera, who has a very distinctive bright voice and carries out peculiar interpretations) superior. One of his conclusion is that the physicality—the bodily communication—of speaking a language is shown through the grains of sound, and such physicality expresses without limitation of linguistic laws. He calls this kind of singing a “genosong”.

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau

Charles Panzera

Now going back to another technical detail in granular synthesis: the use of randomization is very important when one granulates a sound, because this intended unevenness of grain positions would improve the effect, especially of stretched sound. Inspired by the concept of this technology, percussionist Tim Feeney writes that his drum roll is pretty much like a “hand-made granular synthesis”. Each attack is a single grain, and their positions in time and on the drum skin are partially the basic configurations of a synthesis. More importantly he writes that, when he has rolled for a long time and experienced lack of strength, occasional technical failures of rolling in reality brings out the equivalence of a randomization function in the granular process, and that provides a variety of new effects.

If one views the function of granular synthesis as a whole, one would find that the process is still very much like the mentioned paradox in traditional instrument playing. One operates fine control of a sound, and at the same time adds a layer of randomness to it. It seems that human never really left this duality: the “imperfect perfection”. It is then natural to see that, composers in the 21st Century have been trying to combine the technology and the traditional practices together, so as to maximize expressiveness. Live granulation is now available through a faster operation system on computers, and performers can now hear the sound of their instrument being granulated instantly as they are playing. Using the power of granulation, computer live processing is now able to “amplify” human’s physical actions, to transform the sound of the instrument and to expand its musical vocabulary.

Barthes writes that “the ‘grain’ is the body in the voice as it sings, the hand as it writes, the limb as it performs”. It is possible that, after music has been through all these advancement of technologies, people still tend to value behaviors of themselves the most. In the future, with this focus on physical movements, one potential evolution of music would be the merging of relationships between the composers, the performers and the audiences. Technologies would allow the sound in music to be changed by the listener’s behaviors. Overall, art can be regarded as organized expressive human behaviors. The beginning gesture of a piece, the initial splashing of color on the canvas…all points to the motion of the flesh which, although being the most primal and ritualistic, signifies a cry of our existence.

–Yan Yue

Sources:

- Roads, Curtis. “Introduction to Granular Synthesis.” Computer Music Journal 12, no. 2 (1988): 11-13. doi:10.2307/3679937.

- https://www.granularsynthesis.com/

- Barthes, Roland, and Stephen Heath. 1977. Image, music, text. London: Fontana Press.

- Feeney, Tim. “Weakness, Ambience and Irrelevance: Failure as a Method for Acoustic Variety.” Leonardo Music Journal 22 (2012): 53-54.

- Harley, James. “Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001).” Computer Music Journal 25, no. 3 (2001): 7.

- https://lizalimcomposer.files.wordpress.com/2011/07/liza-lim-patterns-of-ecstasy.pdf