In the last few months of 2017, as I was being spiritually pulverized by the ennui of part-making, I found some catharsis in listening to Daniel Vezza’s remarkable 2012-2013 podcast series Composer Conversations, the most memorable episode of which was his interview with his former mentor Martin Bresnick–in which the Yale composition Professor diplomatically recounts his colorful 1970 encounter with Luigi Nono. Bresnick gave a more detailed written account in a New York Times opinion piece some time earlier. To summarize, Bresnick, a moderate socialist, had presented a short film score as part of a Prague conference; Nono, then already recognized as one of the great representatives of the Darmstadt diaspora and Marxist-composer par excellence, was the next presenter. Nono proceeded to give what Alex Ross so vividly describes as “a withering Marxist critique” of this modest work; this Adorno-flavored roast was followed by a presentation of Nono’s own electronic work Non Consumiamo Marx, which, as Bresnick writes, consisted of “surging masses of sound” in which he “could just barely make out the Italian partisan song ‘O Bella Ciao,’ people chanting ‘Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Min,’ and later ‘Mao, Mao, Mao Tse-Tung.’” Apparently, Bresnick was one of three listeners—together with Nono himself and his sound engineer—who managed to sit through this “deafening” collage of socialist fervor; the audience proper had fled, either to construct their counterrevolutionary barricades or to protect their fading hearing.

1970 probably marked the height of what commentators call Nono’s “second style” (which, according to De Assis, spans his output from 1960-1975)—a style derided by critics as one that hits “audiences over the head with superficial sloganism” but hailed by advocates as one that, at least in its best manifestations, produced work of incredibly visceral emotional impact and defiant political solidarity. Six years after Bresnick’s fateful encounter with Nono, however, this second period, which saw Nono the master composer as political activist, came to an abrupt end with …..sofferte onde serene…. (1976), for piano and tape.

What does music from this second period sound like? Non cosumiamo Marx, as Luis Velasco-Pufleau writes, collages text from anti-fascist poetry by Cesare Pavese, field recordings of the 1968 Venice protests (against the “commercial cultural institution” of the Venice Biennale), and anti-De Gaulle slogans sprayed on the walls of Paris, to communicate, as Velasco-Pufleau quotes, the “human experiences of the class struggle of our time” through “electronic composition technique.” Como una ola de fuerza y luz (1972) is a volcanic “concerto” for soprano, piano, orchestra, and tape, which memorializes the communist revolutionary Luciano Cruz, whom Nono admired for his “extraordinary Marxist capacity to fight for Chilean freedom.”

…..sofferte onde serene…, on the other hand, is seemingly apolitical. To begin with, this is the first textless piece Nono composed since his breakthrough work, Il Canto Sospeso—naturally, this suggests a movement away from concrete political content to a more abstract realm of “absolute” music. De Assis writes: “…..sofferte onde serene… has no direct political message or contents.” Indeed, Stephen Davismoon points to an almost Debussyan attempt at impressionism, nodding to the “very subtle shimmering effect” of the piece’s pitch material as an evocation of “the play of light on the lagoon, by the Giudecca in Venice where Nono lived.”

Did Nono, the same revolutionary communist who fervently and publicly decried all the Marxist-aesthetic shortcomings of Bresnick’s film score, abandon politics? None of Nono’s work after ….. sofferte onde serene… ever returned to the explicit activism of his second period. For Warnaby, this was a turn toward mysticism, a kind of religious retreat into what one could call (although it sounds positively ridiculous) monastic communism. Some might say that Nono finally recognized that his work was not particularly successful at initiating revolutions (as, like most art, his music sparked no violent overthrow of capitalist governments), and returned to the “honest work” of pure artistic experimentation.

I intend to argue that …..sofferte onde serene… marks Nono’s forceful return to the capitalist dialectic and is therefore charged with revolutionary communist intention, even if such revolutionary concerns are expressed through a relatively less explicit framework.

The capitalist dialectic

What is the nature of the “capitalist dialectic?” In Hopkin’s short theoretical paper on Nono, he begins with an illuminating quote from philosopher Roland Barthes:

“Communist writers are alone in having imperturbably maintained a bourgeois technique which bourgeois writers themselves have long since condemned—have condemned, in fact, from the very moment of their awareness that it was compromised through the impostures of their own ideology, the very moment, in other words, at which Marxism proved justified.”

There are two important points to draw from this quote which together illustrate the nature of the capitalist dialectic. The first is that bourgeois art is always evolving in an attempt to assert the ideological legitimacy of its context. Here, bourgeois art does not refer necessarily to art made by the bourgeois class but to art conceived in the tradition of bourgeois art—namely, art that presents itself as a teleological successor to previous art. In this teleological succession, every new work—every embodiment of a new “bourgeois” technique—is presented as an endpoint.

Without getting into the semantics, in the traditional understanding of dialectical history (upon which Marx’s conception of history is built), every social structure can be understood as a thesis, which, because it is incomplete or insufficient, immanently produces an antithesis; these two, together, produce a synthesis, a kind of resolution of these two. Yet, each synthesis is merely a new thesis until—one hypothetical day—the resulting synthesis is truly complete. For Marx, this complete synthesis, this full realization of the social dialectic, is communist utopia—the end of history. But before this eternal zenith, history is generated by a cycle of new syntheses. In Hegel’s version of this dialectical history, he identifies the incomplete realization of human freedom in various social structures throughout history and how the evolution of society has made human freedom (gradually) more complete—from the public freedom of the Greco-Roman world, to the individual intellectual freedom of the Reformation, to the constitutional freedoms of contemporary politics.

When an artwork asserts itself as a final synthesis, it creates the brief illusion that the capitalist system in which it was produced—an incomplete synthesis—is somehow a final synthesis of social structure. We see in neoclassicism—in works like Stravinsky’s Octuor—a move to objectivity: like newly-ordained adults, neoclassicists turned with disdain from their youthful nationalist fervor and romantic excess and proclaimed a musical language of what Taruskin summarizes as “purity…austerity…dynamism…and transcendent craft.” Mason Bates provides a more recent example: as Ritchey writes, “Bates’s use of technology and cool techno beats” in The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs is served as apparent evidence that we have moved past the “elitist culture” that once characterized classical music. But just as contemporary audiences understand that the “moral maturity” of the 1920s was far from the endpoint of moral evolution and that Stravinsky’s attempt at objectivity can only register today as a kind of archeological artifact (really by ignoring its inherent eurocentrism and imperialism), I would hope that future audiences would agree that the institutional inclusivity purported by Bates’s opera is really insufficient and that incorporating “techno beats” is far from the endpoint of institutional openness.

What characterizes the capitalist dialectic in music, then? It is characterized by an endless push for novelty, which is manifest in music in the construction of different sound relations and the uncovering of new sonorities. These novelties quickly become outdated, because their ideological foundations—the social context upon which they are built and in which they must function—are incomplete. Novelty is foregrounded: when one listens to the Octuor or to The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs one hears the “radically new” neoclassical texture and techno-infused stylistic plurality, respectively—and only after that the myriad other constructive elements that constitute the pieces.

The second takeaway from Barthes’s quote is that communist artists have somehow created a space apart from this capitalist dialectic. His criticism is primarily against socialist realism: by regressing (unironically) into old idioms, communist practitioners of socialist realism essentially divorce themselves entirely from this unquenchable drive towards novelty. It was entirely possible for a composer living in the capitalist world of the 1980s to ignore the work of Shostakovich, but almost impossible to ignore the work of Stockhausen. This is problematic for communist composers, since communism is fundamentally a synthesis that emerges from the capitalist dialectic. In traditional Marxist theory, communism cannot emerge independently from capitalism: as Marx writes, “between capitalist and communist society lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the other” (my emphasis). Therefore, in a world still far from total communism, the capitalist dialectic—both in the broad social sense and its specific music-historical manifestation—are the vehicle for the realization of communism.

A truly revolutionary communist composer, therefore, should be engaged directly with the capitalist dialectic—and thereby enacting the transformation of capitalism into communism. Specifically, the communist composer must be actively pushing the extreme forefront of the avant-garde. As Ritchey writes in the article linked to above, Mason Bates’s attempts at bringing techno into the classical concert hall are half-hearted—but this level of “middling music” is only possible because this is, unfortunately, the very fringe of the avant-garde. Because there are essentially no composers engaged in this vein of the capitalist dialectic who are working with challenging audiences through bringing in radically experimental techno elements, Bates can rest secure in the illusory “edginess” and “inclusivity” of his music. The communist composer must smash such illusions and thereby drive music forward on its teleological progression towards complete synthesis.

Returning to the dialectic

Nono’s work can hardly be criticized as socialist realist, but his work from his second period effectively departed from the capitalist dialectic. De Assis writes that the elder Nono “realised…that his previous works, with all their explicit political engagement, had been easily misunderstood as bare ‘pamphlet art,’ their political contents shadowing their intrinsic musical features, so that the latter were not properly perceived by the listener.” These works contained techniques which could be associated with the forefront of the avant-garde, but such techniques were not foregrounded by the music: that Nono was using radical new approaches to electronics and space was rarely as apparent as the fact that he was having singers shout anti-capitalist slogans. Non consumiamo Marx, for instance, works with techniques of documentary collage (being simultaneously explored by Luc Ferrari in the late 60s) and the threshold of listening pain (which is a central concern in the work of Maryanne Amacher in the late 70s); these experimental traits are subsumed into the idea that the piece is a work of angry protest.

…..sofferte onde serene… returns to the capitalist dialectic, both because it is radically new and also because it foregrounds its newness. What is new in …..sofferte onde serene…? Davismoon (in the article linked to above) recognizes the remarkable relationship between electronics and piano. The placement of speakers, in contrast to Stockhausen’s preference for circular spatialization, is intended to expand the spatiality inherent in the piano; the electronic sounds, which exist neither in “opposition, nor in counterpoint” to the electronic sounds but instead stem from the physicality of Pollini’s piano playing—“the tonal attacks, the extremely articulated percussion on the keys…nullifying the alien mechanical nature of the tape”—prefigure the centrality of gesturality in the major works of Helmut Lachenmann (consider the centrality of gesture to Lachenmann’s own analysis of Reigen seliger Geister) and Salvatore Sciarrino (see especially pages 23-27), in addition to the idea of electronic liveness, which spectral composer Jonathan Harvey addresses almost two decades later in his seminal The metaphysics of live electronics. Harvey considers how electronics can simultaneously produce “sounds that have no, or only vestigial, traces of human instrumental performance,” in addition to sounds that merge with instruments “in a theatre of transformation,” in which “no-one listening knows exactly what is instrumental and what is electronic”; such varying degrees of transformation are explored in Nono’s tape, from pure recorded piano pitches to heavily filtered thumps.

Particularly notable, however, is how Nono foregrounds this novel relationship between live sound and electronics. This is Nono’s only mature work for solo piano. The choice of instrumentation is doubly important: firstly, the piano can only lay claim to a very limited domain of timbres, since, in contrast to almost all other string instruments, the location of attack (and therefore content of harmonic spectra) is fixed. As I mentioned above, …..sofferte onde serene…, through its almost prophetic investigation of the gesturality and physicality of performance, presages Harvey’s investigations into degrees of electronic transformation—because the sound of the piano is essentially fixed, degrees of liveness are optimally perceptible. In other words, because there is essentially one kind of untransformed sound, all transformed sounds can be evaluated for their degree of transformation in relation to this untransformed sound.

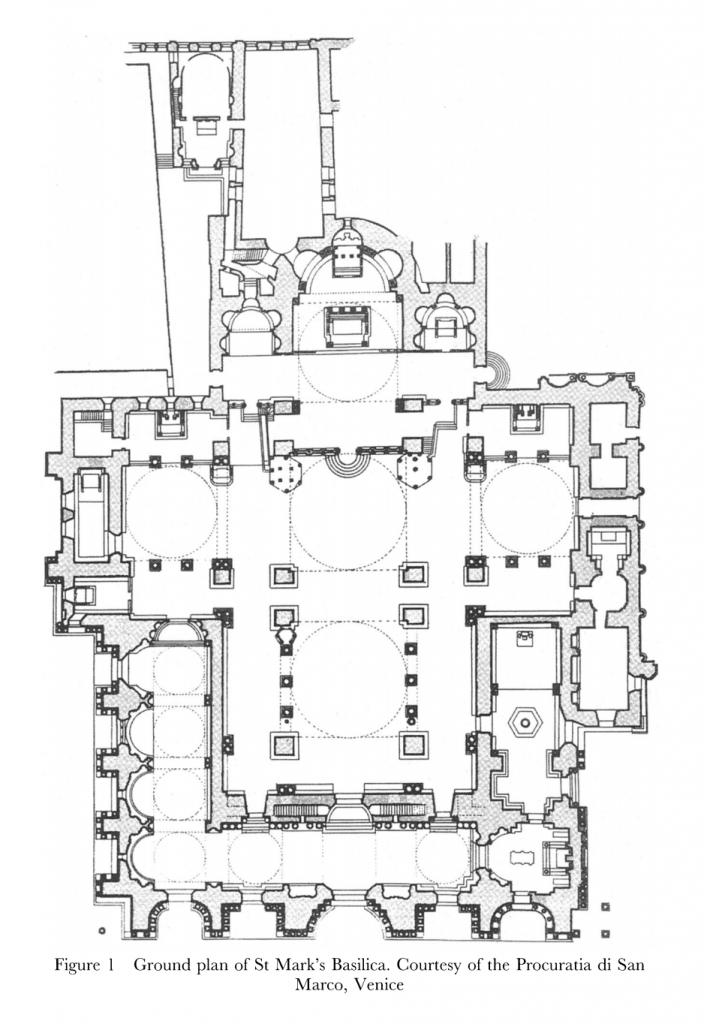

Secondly, the piano, in contrast to the grandiose public theatre of Nono’s second period—much of it intended to be played for workers in industrial settings, as Warnaby notes in his aforementioned article—the grand piano is a fixture of the bourgeois concert hall. Nono’s choice of instrument was a literal re-entry into the capitalist performing space, a forceful intrusion into the capitalist dialectic.

At least as important as the choice of instrument to the presentation of this “newness” is the use of form, in particular its relation to time. As Davismoon notes, …..sofferte onde serene… uses a kind of non-linear temporality. In music where timbre, particularly the perception of live and electronic timbre, is so central, a linear, narrative temporality can be a severe distraction, since one almost automatically becomes engaged with the flow of musical material rather than with specific sonorities. Davismoon analyzes the temporal fluctuations of Nono’s work to show how it creates a kind of wave-like ebb and flow of intensity such that, as he quotes Kramer, “the result is a single present stretched out into an enormous duration, a potentially infinite ‘now’” in which “whatever structure in the music exists between simultaneous layers of sound, not between successive gestures.”

By suspending narrative time, Nono allows us to access, according to Spangemacher, “the tiniest corners of harmony…most isolated and inaccessible regions of sound.” It is precisely this ability to create suspended time, to force us to experience sound at the most microscopic level, that characterizes Nono’s work from …..sofferte onde serene… onwards.

In Nono’s second period, radically new sonorities were often suppressed perceptually into monumental narrative frames and the centrality of political messages; in Nono’s late work, he is able to bring us into an incomparably intimate and contemplative encounter with such novel sounds. The communist composer, as exemplified by Nono’s late period, is the destroyer and creator of myths: his work is the storm of progress, propelling the dialectic forward until its inevitable conclusion. To quote Walter Benjamin:

“[The Angel of History’s] face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”

-Haotian Yu