The essence of technology, according to philosopher Martin Heidegger, is, in his own jargon, a clearing: specifically, technology is a kind of worldview that reveals—or more often than not imposes—an essential purpose to things. For those who are interested in reading Heidegger’s original paper, it can be found here.

His most important points, for our purposes, are as follows:

- Things by themselves simply are—they do not need to serve any purpose (a tree simply is)

- Technology is the imposition—the forcing-on—of purpose on things (technology imposes purposes on a tree—as part of a shelter, or the handle of an axe, etc.)

- Technology is therefore a violation of the freedom of things, which prevents us from appreciating them in-and-of-themselves (we view the tree as a means to end; this perspective degrades our experience of the tree)

Before recording devices, free sonic beings in-and-of-themselves did not appear in formal concert settings. All music-making, pre-phonograph, necessitated a technological manipulation of an object outside of its natural context. The bone flute, perhaps the most technologically “primitive” of all instruments, is still relatively technological in its appropriation of the bone—which doesn’t seem remotely musical by itself—as an end to musical sound. Or, from another point of view, sonic experiences, pre-phonograph, were marked by a clear partition between outdoor and indoor sounds: there was the natural world itself (the world of free sounds) and the technological world of the concert hall.

The idea of found sound, then, should be absolutely revolutionary—at least from a Heideggerian point of view. Found sound—the use of recorded, so-called “non-musical” sounds in an “indoor” setting—is perhaps the very first instance of a sonic-being appreciated in-and-of-itself in a concert hall milieu. Its history, therefore, outlines a story of ethics, framed around changing conceptions of the role of the “unadulterated” sound. We will attempt to dissect this narrative in four seminal works of electronic music.

1. Pierre Schaeffer: Étude de Bruits

Found sound entangles itself with philosophy; it is not surprising, then, that is has been subject to much very polemical writing. The first major works of found sound composition, musique concrète (music made by manipulating recorded sound) were entrenched in the typically heated debate of the post-1945 (postwar) generation of composers, many of them heavily invested in creating a new kind of electronic art distinct from the burdened music of the past (for a more detailed discussion of that and the following, see chapter 1 in Joanna Demers’s Listening Through the Noise: The Aesthetics of Experimental Electronic Music).

Most discussions of electronic music in general (including this one) begin with musique concrète, but that umbrella term encompassed at least two very different perspectives to found sound. Indeed, Pierre Schaeffer, who almost single-handedly invented musique concrete in his Paris Studio in the 40s, wrote music of constantly evolving characteristics—not least as a result of the technological limitations of his times, and these divergent approaches, although not by themselves always philosophically grounded, positioned found sound radically differently in relation to Heidegger’s notion of being-in-and-of-itself.

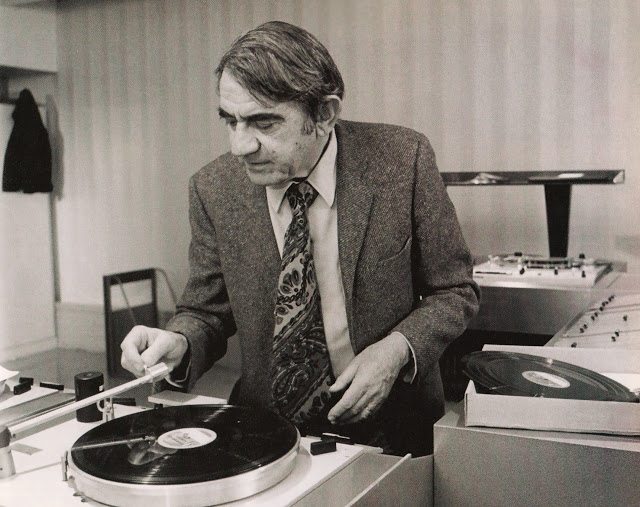

This first and earliest work of musique concrète, Étude de Bruits, was composed on a shellac record disk, such that techniques nowadays considered commonplace—transposition, looping, filtering—were manipulated excruciatingly by hand. The limits of this “primitive” technology can be heard in the piece. This piece contradicts, for better or worse, the ideals developed in Schaeffer’s later philosophical writings (which I will discuss shortly): this is a kind of musique concrète where sound sources are easily identified—and indeed come with whole packages of connotations.

What might Heidegger have thought of these musicalized trains and sauce pans? His questions may have revolved around the intended affect of such a piece: it is a settled fact that the first étude recalls a running train, but to what end? My personal impression of the piece is primarily of a filmic experience. There is a sense in which the grainy audio recalls a likewise visually grainy old black-and-white film, populated by the objects suggested in the music.

Is this an experience of sound as a being-in-and-of-itself? It is rather easy to suggest that Schaeffer fails to achieve this kind of experience because the recorded sound becomes a technological means—and therefore an unfree being—of evoking a filmic quasi-narrative. And yet, on a certain plane, this kind of filmic sound already suggests a lesser degree of technological manipulation than instrumental music. Traditional instrumental music subsumes the identity of the object within its sound, such that when we hear, say, a violin, we do not hear it as a sound stemming from an object but as a sound, to which the object is subservient. These Études are, to my ears, something different: no such hierarchy exists between the train and its sounds.

2: Pierre Schaeffer: Étude aux objets

Schaeffer eventually published his musico-philosophical musings in several writings. Many of his ideas are summarized in Demers’s book—Schaeffer turns his back on the filmic sounds of Bruits, the failures of which he blames on the technological limitations of the 1940s. With the invention of the more versatile tape recorder, Schaeffer experienced a degree of artistic freedom which enabled him to experiment with “emancipated” sound, much inspired by Husserl’s phenomenology (as Dostal writes, Heidegger’s work is based on the framework of Husserl’s thought). As Demers writes, Schaeffer attempts to create a free sound-being “through the removal of visual cues” and “through the intentional disregard of the perceived sources and origins of a sound.”

What this sounds like in Étude aux objects is a rather complex collage of sounds—sounds of obviously physical/natural emanation, but of imprecise origin and context. This, for Schaeffer, was a liberated sound-being. Schaeffer is in part addressing his own Études aux bruits and that technologization of sound, in which sounds become mnemonics, markers for objects: in this new musique concrète, Schaeffer advocates a kind of music which leads us to, one, hear the sound as being real, and, two, hear the sound as having interest in and of itself. Sounds must be heard as beings distinct from visual entities.

Demers’s book captures some of the polemic that surrounded this claim. While Schaeffer’s ideas—on paper—seem to suggest a true “autonomous” and free sound being, Demers notes that composers, especially of the younger generation (the infamously argumentative young Pierre Boulez perhaps leading the charge), had doubts about a sound’s ability to separate itself from an outside context without being turned into an instrument (which would eliminate its philosophically vital distinction from instrumental music).

Such complaints are clearly heard in the music. Listening to Études aux objets, one is compelled to guess the origins of the sounds, and it is difficult to hear the piece without feeling that there are two contradictory layers of organization—as Lévi-Strauss notes: one, the implied contexts and worldly emanations of the sounds, the implications of which suggest a network of relationships, and two, the actual organizing principles of the music. For instance, a sound similar to a car horn followed by a crumpling or crashing sound automatically suggest their own narrative, such that this sequence interferes with a more abstract, composed structure.

I have mixed feelings, however, about the value of such objections to Schaeffer’s thought. Heidegger’s thought is centered around the idea that our understanding of the world must be unlearned: likewise, is it not possible to unlearn our mnemonic understanding of sound?

3: Karlheinz Stockhausen: Kontakte

Supposing that Boulez et al. had touched on truth in their rejection of Schaeffer’s “autonomous” sound-being, it may be the case that a truly freed sound must speak of itself. Citing Stockhausen’s Kontakte as an example of found sound is a bit of a stretch, since the sounds are entirely synthesized—made from scratch—from basic wave generators, but my thinking here is that, in Stockhausen, the attempted autonomous sound-being is sound itself, detached from any specific context. In The Concept of Unity in Electronic Music, Stockhausen illuminates how works like Kontakte stem structurally from acoustic principles. One particularly spectacular instance is a long and dramatic glissando (which Stockhausen draws out in the air rather spectacularly in a 1970s lecture here) which illustrates how a single pitch can be lowered until it is a series of attacks—illustrating that timbre/pitch and rhythm exist on the same continuum. Like in some modernist architecture, in which light is not used merely to illuminate spaces but to be savored on its own as an independent architectural entity, sound here is not merely a material for music, but the driving force behind the music itself.

4: Hildegard Westerkamp: Talking Rain

One of the criticisms of Schaeffer’s earliest works is, as mentioned above, the apparent mnemonic quality of sound imposed by found sounds of obvious origin. One can reject found sound’s context—as Schaeffer—or disregard found sound entirely—as Stockhausen—but it is indeed also possible to go the opposite direction and embrace the context of found sounds as the primary element of musical organization. Soundscape composition, often described as acoustic ecology – a school of electronic music first written about extensively by Canadian R. Murray Schafer (no relation to the French Schaeffer), is such a musical movement.

As Demers writes, soundscape composers recognize that sounds are inexorably linked to an environmental context. Whole sections of pieces consist of field recordings of what one might call ambient sounds, often with the intent of preserving the unique soundscape of a locale, be it an inhabited or pristinely natural one. Such recordings are often achieved with binaural recording systems, replicating a listener’s experience of the sound with maximal precision. In a sense, soundscape composition is a kind of virtual travel for the ears alone. In addition to being “unadulterated” sound in a literal sense, the idea of soundscape can also be seen as Heideggerian in that it recognizes that the very definition of being implies being part of an environment, what Heidegger calls facticity. Yet, this claim can be problematic. In Talking Rain we have a sequence of environmental milieus, not an actual field recording that runs for 15 minutes. One can argue that the milieus are extracted and technologized to serve the structure of the piece: the recordings lose their freedom in the context of a larger musical structure. On the other hand, I would argue that each soundscape is sufficiently immersive on its own to become autonomous, but ultimately this relies on a specific mode of listening.

Indeed, as with all previous attempts to liberate sound from technology, what is perhaps most important is the perspective of the listener. It is the listener who imposes purpose, but it is also the listener who frees sound by the act of listening.

-Haotian Yu