What does “passed” mean for a person when for each of us the past is the bearer of all that is constant in the reality of the present, of each current moment?

Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time

Luigi Nono (1924-1990), one of the foremost pioneers of avant-garde music in post-war Europe, is also recognized for his fervent, left-wing political engagement. Following the stage works Intolleranza 1960 (1961) and A floresta é jovem e cheja de vida (1966), his electronic composition and explicitly political statement Musica-Manifesto n. 1 (1969), and Como una ola de fuerza y luz (1972) for soprano, piano and orchestra, his political activism culminated in Al gran sole carico d’amore (1972-4), an ‘azione scenica’ (scenic action) which was premiered at La Scala on 4 April 1975.

Nono expressly reminded Ricordi, his publisher, to avoid the traditional classification of a staged musical work as an opera. Certainly the eluded genre has been long bound with bourgeois connotations; the opera, besides the ample potential for commercial success and the institutionalization of vocal training, is also bound with a specifically linear style of storytelling. This convention had not been broken for almost 200 years since the solidification of the opera culture during the eighteenth century. Nono’s Al gran sole carico d’amore, however, does not unfold in accordance to the linear convention. Hybrid historical events and social incentives intertwined, their coherent interrelationship to each other very much effectively accomplished at the first place by an equally hybrid literary input. Nono adapted an anti-symbolism, affective and highly logical method to present collective will; since communist writers are a conduit through which the people illustrate their wills and utopian images, there lies a moral obligation to obliterate the boundary between the individual activist and a group of activists. Therefore, what originally is represented by a singular character in the literary source may be assigned for multiple voices or dispersed choruses in Nono’s work – a collective search for truth and communist utopia. The ordering of historical events, poetry references, and dramatizations is not confined to a temporal way of thinking, but is choreographed upon a plane of historicity which seamlessly morphs from one stage to another, from the present to the past. Time is will; the dolcissimo singing is the gravity which creates tremendous character in the human agents.

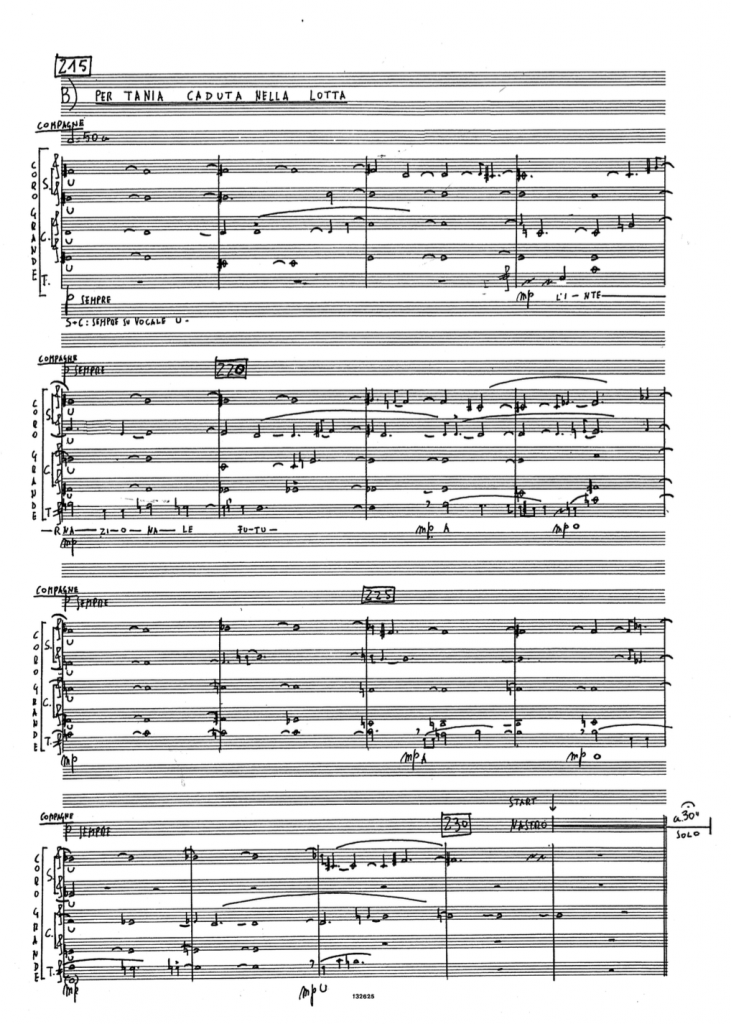

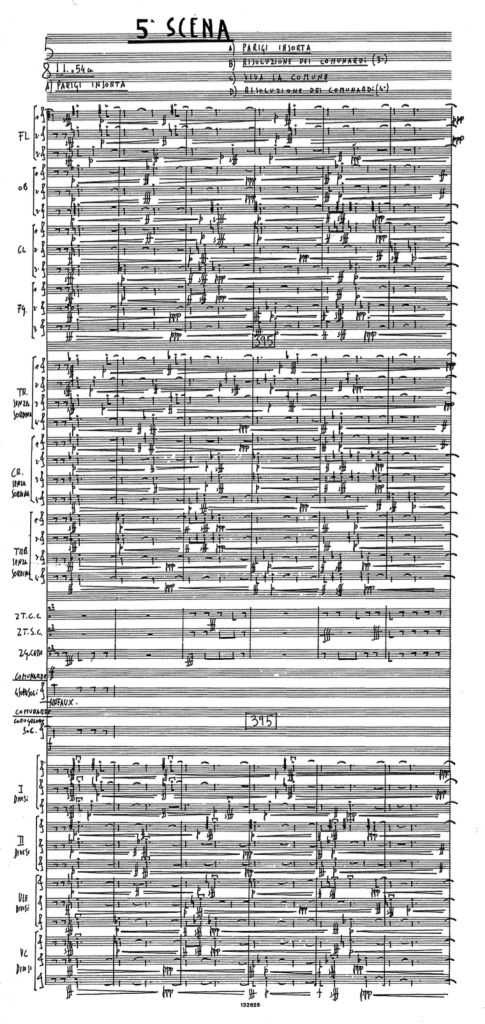

Another major characteristic of Al gran sole carico d’amore, and indeed many of his politically engaged compositions, is the utilization of protest songs and communist anthems, which, in spite of the fact that these songs all conform to tonal practices, still maintains a prospective, forward-looking character. In the liner notes of Lothar Zagrosek and Staatsorchester Stuttgart’s 1999 recording of the opera, Klaus Zehelein writes that “a crucial element of [Al gran sole carico d’amore] is that meaning is created, and that it is not, as in neo-Romanticism, a case of using expressivity as something which already exists. Rather, it is a matter of redefining it through syntax (trans. Alfred Clayton).” Indeed, quotations of tonal melodies, in an ‘atonal’ and teleological context, are often intended to invoke some kind of nostalgia or distance, usually characterized by inertia and the stark contrast with dissonant, actively fantastical and expositional passages; examples include the Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto, who contextualized a Carinthian folk song as the revelation of origin behind the cradle-grave analogy, and George Crumb’s Black Angels, who included the theme of Schubert’s Death and the Maiden and utilized it as an interlocutor of micro-density realms. On the contrary, Nono directly intruded into the interval content of the songs in a way that the songs cease to operate in a tonal logic; intervals, liberated from tonal contracts, enter the terrain of spatial considerations and negotiations. Jonathan Impett notes that, in Nono’s 1969 work Per Bastiana – Tai-Yang Cheng, “having analysed the limited interval content of The East is Red, Nono puts it at the centre of a wider pan-chromatic, all-interval interval matrix. The fragments thus produced explore the expanded pitch space step by step, until the pitches and intervals of the melody itself gradually emerge from their chromatic negative through the eight passages of the third section. (278)” Intervals denote space; the reality of expression lies in the peculiarity of individual spatial components and the composer’s ‘hegemonic’ organization. The shades of tonality are, once and for all, extirpated along with the relics of nineteenth-century romanticism which characterized the European bourgeois. Allying himself with Gramsci’s analysis of political hegemony, one of the main tenets of communism, Nono erased the difference between space, progress and history; intervals are like the resonating body of vociferous persons, articulating their demands and inviting adversaries – other intervals – to enter a socialist dialect, an perpetual process of compromise. His radical inventions were also a means to denounce a then-prevailing antithesis of his approach: that the use of revolutionary songs without a radical reworking on their musical profiles is, in other words the lack of radical participation in the musical/teleological prospects, is lethargic and, ultimately, bourgeois and authoritarian.

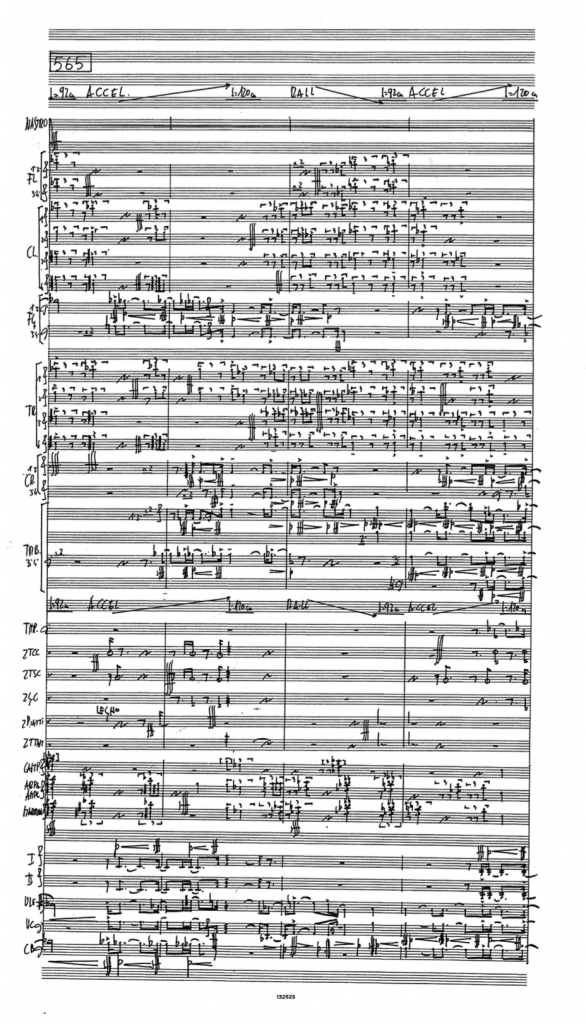

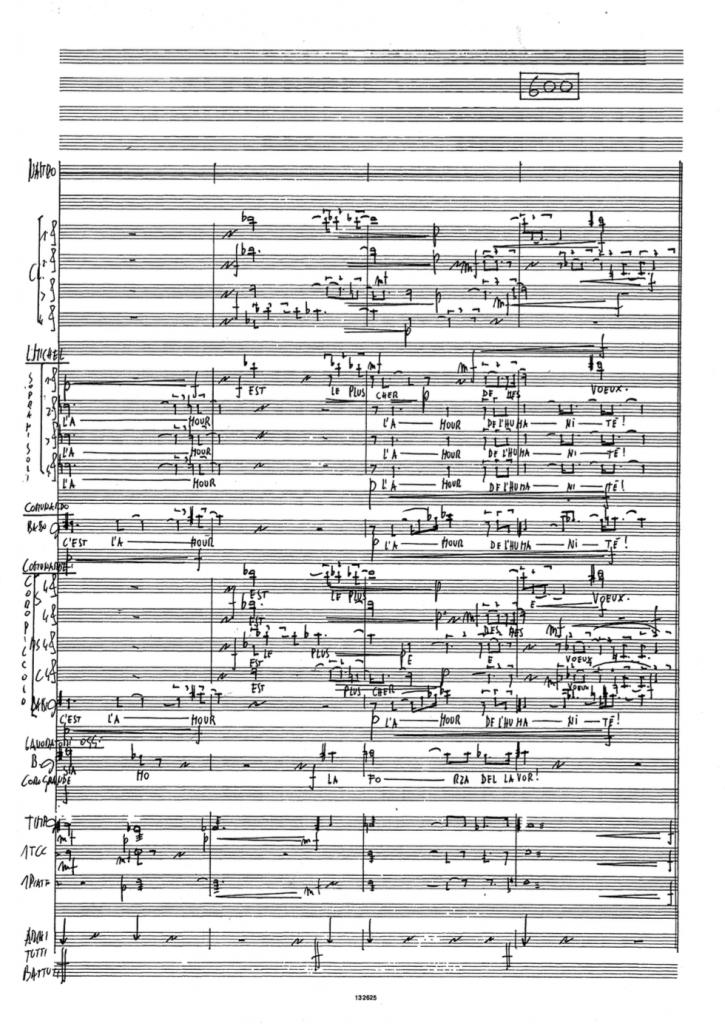

I/1

I/1

I/2

I/2

I/3

I/2

I/4

I/4

I/5

I/6

I/6

II/1

II/1

II/3

II/4

II/4

II/Finale

II/Finale

But in what ways does Nono’s scrupulously radical process of intervallic recontexualization reprimand a chronological time? In what ways does Nono’s compositional method correspond to the moral objective of azione scenica, the “expression of history (Zehelein)”? And how are deviations from this practice rendered ‘immoral’ or ‘irresponsible’? Perhaps we can take a departure to appraise neo-romanticism to clarify this issue.

Intending to revive conventional idioms and musical (especially tonal) practices, neo-romanticism is, needless to say, a polar opposite of Nono’s Gramscian approach of music; it is music “using expressivity as something which already exists.” In the remainder of this post I intend to argue how time and material are essentially the same, and how the mediocrity of material selection and utilization of neo-romantic music would imply not only a false representation of time but also, at worst, moral defects.

In 2017, Mason Bates’s opera, The (R)evolution of Steve Jobs, received its premiere. Although it has won a positive public appeal, critics have expressed discontent about the incoherence of musical ideas – largely due to Bate’s heavy dependence upon ‘pastiche’ – and have found it one of the detriments that made the opera unconvincing, along with the opera’s ‘moral vacuity’ and its ‘clichéd, fraudulent narrative arc.’ Having assessed Nono’s azione scenica, I would add that the fourth detriment to this opera is the banal understanding of time typical to neo-romantic composers. Andrei Tarkovsky, arguably one of the greatest film directors of all time, considered morality and human conscience contingent with time, which “in its moral implication is in fact turned back. (Sculpting in Time, 58)” Why does the adherence to morality require a different understanding of time? How does Bates’s opera subscribe to the ostensibly factual conception of an ‘irreversible time,’ despite the seemingly unconventional, non-chronological plot of Jobs’ life? How does Bates’s toying around with pastiche relate to this issue at all?

Unfolding the argument from the last question:

“[…] the first essential in any plastic composition, its necessary and final criterion, is whether it is true to life, specific and factual; that is what makes it unique. By contrast, symbols are born, and readily pass into general use to become clichés, when an author hits upon a particular plastic composition, ties it in with some mysterious turn of thought of his composition, loads it with extraneous meaning.”

Andrei Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time

The lack of specificity and factuality is manifest in the ubiquitous troping of pastiche in the opera; religious themes are represented by ‘orientalist clichés: breathy pentatonic flute, gongs, and prayer bowls,’ the musical-mathematical analogy by a literal quotation of J. S. Bach’s music, calamity by ‘self-consciously “modernist” idioms,’ etc. The maker of a polyscreen film is forced to “[reduce] simultaneity to sequence, in other words of thinking up for each instance an elaborate system of conventions (Tarkovsky, Sculpting in Time, 71).” Bates’s approach to semantic articulation also necessitates a similar solution: to reconcile irreconcilable musical/referential material by means of sequence and clichés. As a result the opera is neither specific nor factual; but how does this lack cause the opera to succumb to linear time?

The concept of linear time, according to Tarkovsky, stems from a semantic reading of cause and effect – it itself not more than a failure to see the “mutual dependence” of cause and effect of “inexorably ordained necessity”; “The link of cause and effect, in other words the transition from one state to another, is also the form in which time exists, the means whereby it is materialised, in day to day practice. (58)” A progressive reading of cause and effect would reveal the reversibility of causality and its primary agent – conscience – and it is the same progressive spirit that makes a plastic composition ‘specific and factual.’ In short, a materialised means automatically leaves the expressive terrain and is bound with troping, therefore is utilized in the same semantic realm where materialised, linear ‘time’ belongs to; by contrast, an idea or a statement charged with specificity and factuality is able to register itself unto the dialectic of truth and the conscience “inherent in time itself.”

Therefore, the use of techno signifiers and many other instances of pastiche in Bates’s opera in fact signifies an absence of moral bearings. The opera, by assorting and situating these symbols in their representational, ‘literal’ forms, countermands the provocative responsibility of an artwork and becomes a temple of archaic semantics; it is therefore devoid of truth, of individuality, and of expressive potential.

Gramsci considers the popular song as a prism of intentions and empirical dimensions: “What distinguishes the popular song of a nation or a culture is not its artistic origin or historical origins, but its way of conceiving of the world and life, in contrast with official society (Gramsci, Letteratura e vita nazionale, 1950),” Nono’s Al gran sole carico d’amore extended – perhaps extrapolated – Gramsci’s thesis into the exigent circumstances of post-war Europe and demonstrated the means of social unity through an unrelenting procedure of demarcating and demolishing dialogical spaces which finds momentary utopia within both internal and external manifestations of the world. As a composer, he internalized this historicity as well; the labyrinth of communist activities has formulated a self-sufficient dialectical terrain which, along with his impeccable erudition, caused him to gradually consider historicity in a different way. May I conclude this blogpost with Nono’s illuminating contemplation of himself:

I don’t aim to liberate myself from the shadows of the past.

Nono, letter to Pestalozza, September/October 1981

I don’t repudiate my work, thought and acts of the past.

I have neither need nor motive to liberate myself from them.

I am just seeking to broaden and deepen my thought in my work, in my life.

I am also seeking to understand various dismemberments that have taken place within me (lacerations of various types leading to other discoveries of diverse quality and with various consequences) […]

I am simply discovering other possibilities […]

What I am studying literally upsets me because it opens me up to other thoughts, it doesn’t just make me question myself but makes me surpass the limits of the preceding thoughts and sentiments (why repudiate them if I come from here, why refute them if they are continuing in other ways in me?????) and at times in the joy of such intra-listening [intraascolto] I find myself alone.

– I-Hsiang Chao