The All of Bach project is an undertaking by the Netherlands Bach Society—the legendary Dutch period ensemble “on the vanguard” of Bach scholarship and performance practice—to produce a recorded video anthology of the entire opus of the Eisenach master. For instrumental works not scored for their core ensemble they have reached out to soloists, many of international repute: harpsichord works have been recorded in domestic settings, in seeming homage to the musical interiors of the Dutch Golden Age. Christian Rieger’s filmed performance of the charming E major Prelude and Fugue—if one ignores the absence of ruffled collars and tights—grants one entry to a living Vermeer canvas.

A different artistic lineage, however, is being perpetuated in what is by far the most popular video of the extant harpsichord collection: in Jean Rondeau’s breathtakingly sublime rendition of the Aria mit 30 Veränderungen, better known to posterity as the Goldberg Variations, BWV 988, director Jonas Sacks and cameraman Petr Cikhart grant us a camera obscura of a setting perhaps even more intimate than the domestic interior—the alchemical lair of the recording studio. This union of the Goldberg Variations and the recording studio milieu inevitably invites comparison to Glenn Gould’s 1981 video rendition of the same work, directed by Bruno Monsaingeon and released as the third volume of Glenn Gould plays Bach.

Like Sebald inheriting Kafka’s propensity for fable or Malevich inheriting Kandinsky’s spatiality, the continuation of a tradition asserts, by itself, a strong aesthetic position. Monsaingeon’s 1981 video recording can on one hand certainly be regarded as a visual artifact that merely accompanies Gould’s audio recording, but it is more usefully understood as an exposé of Gould’s fundamental aesthetic beliefs. We know this is the case because Gould was obsessively involved with personally perfecting every aspect of his publications—the interview he did with Tim Page on this particular recording, for instance, was entirely scripted, tangents and bad jokes included. By preserving the most important aspects of Monsaingeon’s production—and thereby preserving Gould’s deliberate methods of self-presentation—Sacks’s video clearly conservates Gould’s core aesthetic values.

As is well-known, Gould abandoned concertizing early in his career and devoted himself to the recording medium. In his essay on the ideological overlap of Glenn Gould and Marshall McLuhan, Paul Théberge identifies how Gould’s embracing of the studio can be understood in light of some of Gould’s key ideas. To begin with, Théberge identifies Gould’s use of technology “as a way of maintaining contact with, and a way of protecting himself from, the outside world.” Gould exploits the communicative potential and ritual-free medium of recording by prefacing his performance with a discussion, with director Monsaingeon, about his choice of takes. Like in Gould’s many telephone-only friendships, he is enabling, via the video medium, a particularly intimate mode of communication—an insight into his creative process—while simultaneously dictating the terms of this communication. Rondeau’s performance is similarly paired with an expository video:

The very existence of such a video exposition already indicates a clear break from concert etiquette and therefore the traditional primacy of live concert performance (and the distancing of audience and virtuoso). Théberge cites Gould’s aversion to the traditional concert hall performance, his critique of the concert hall as a symbol of “musical mercantilism” and a means of “ego-gratification.” Both Sacks’s and Monsaingeon’s videos evade suggestions of the concert hall milieu. There is a liberalization of perspectives—extreme close-ups, unusual vantage points (including the prominence of low point-of-view shots in both videos), and camera movement. Significantly, there are visible attempts to eradicate the concert hall milieu (and its bourgeois stuffiness). This stands in contrast to the traditional approach to filmed performance, in which, as Melina Esse writes, videographers aim to preserve the illusory liveness of staged performance, via “the persistent interpenetration of the live and mediatized such that there remains no clear distinction between the two,” and indeed often by foregrounding the recording milieu as a localized social context; see the lengthy virtual concert-hall tour that precedes this D minor cello Suite production from the Netherlands Bach Society:

In Gould’s case, this emancipation from the milieu is accomplished by the chiaroscuro lighting and darkening of the mis-en-scène, such that any sense of a fixed space/locale/establishment is obfuscated; in Rondeau’s case, the same is achieved by the use of a large, modernist and (most importantly) chairless recording hall, which seems hermetically sealed from the outside world and therefore inaccessible to intruding audiences. Additionally, both directors evade the conventional direct profile view of the typical concert-goer:

Théberge quotes Gould’s assertion that, in the age of “electronic culture,” “the performer’s once sacrosanct privileges are merged with the responsibilities of the tape editor and the composer,” and, indeed, that “the Van Meegeren syndrome…becomes rather an entirely appropriate description of the aesthetic condition of our time.” The Van Meegeren mentioned here was an infamous Vermeer forger: Gould believed that the forgery of the doctored recording was no cause to be shameful. Indeed, as Edward Said writes, Gould’s most prominent ability as a pianist was the creation of a kind of “art that tries to show us its compositional activity still being undertaken in its performance.” No aspect of this compositional activity needed to be hidden.

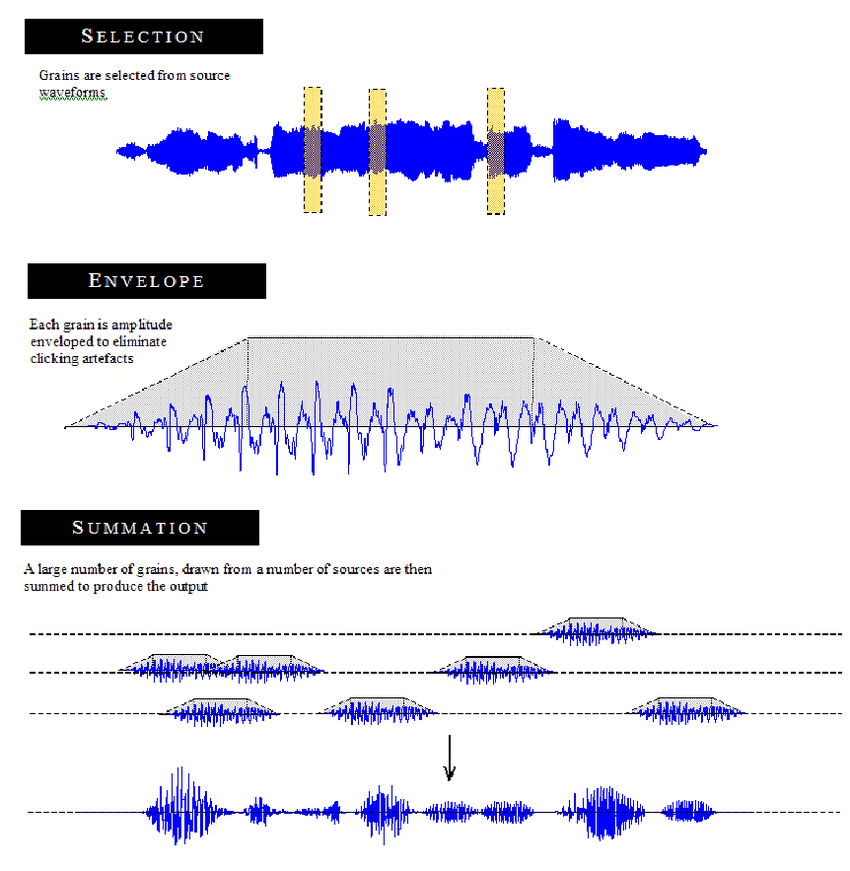

This attitude towards open process is reflected in the cinematography of the opening Aria in Gould’s 1981 performance rather heavy-handedly by a slow pan from the mixing console to an engineer’s window-filtered view of the pianist. Sacks’s cinematography accomplishes the same effect with more subtlety: a tall microphone-stand towers over Rondeau and his instrument, often visible, hardly hidden, but not exhibited as a novelty—in fact, presented as an expected, mundane fixture. Abrupt changes in lighting cue us to the multiple-takes and post-performance patchworking involved.

These cinematographic choices reveal that video recordings can reveal, often on a subliminal level, core aesthetics of the performer in question. Not surprisingly, key aesthetic differences in Gould’s and Rondeau’s approach to the Variations are also reflected in the videography. I’ll mention just one for the sake of brevity, although, as is the case for most such comparisons, countless details differ. Gould was largely uninterested in the physical aspects of piano performance; as Anca Aleman notes in her essay “Non-Judgemental Musical Criticism” (as found in Gould and Variations) Gould was hardly interested in the distinct sound of the piano and the physicality involved in its sound production. He could have been playing harpsichord, organ, or string quartet—what was vital was the clarity of polyphony. As Théberge notes, Gould’s pianism maximized clarity to bring out the most subtle layers of musical structure and detail, a direct antithesis to the “cavernously reverberant” sound of the traditional concert hall. Gould removes the fallboard, such that he is receiving the most direct—and hence clearest—sound output of the instrument, and the video largely focuses on the space surrounding Gould and his head: the space where the sound is being conceptualized, processed, and re-conceptualized, rather than the space from where the sound emanates and dissipates. Rondeau, on the other hand, according to his video introduction/interview to his recording, is intensely drawn to the harpsichord’s sonority, something “delicate and fragile,” and its lute-like physicality. Indeed, he describes the Goldberg Variations as an “ode to silence,” even a “caress” of silence; it is no surprise, therefore, that Sacks tries to capture this sonic caress by featuring long close-ups on the harpsichord’s visually delicate strings and aerial shots of the cavernous recording hall, in which one can almost see the single diminutive sounding body, the harpsichord, dissipate its energy into a vast space of responsive silence.

I was somewhat surprised to see that audience reactions generally avoided Gould allusions—even besides the numerous videographic parallels I’ve pointed out (which clearly place Rondeau’s performance as a successor to Gould’s thought), Gould’s legacy hangs over the Goldberg about as much as Herbert von Karajan’s hangs over the Berlin Philharmonic. We could perhaps ascribe this to the fact that, as Théberge notes, “in an economic system that seeks to produce not only the objects but also the conditions of consumption” (i.e. the economic system of our current digital capitalism) “it is the recording and broadcast industries that should be regarded as the most dynamic symbols of that system,” a phenomenon that has, in effect, realized some of Gould’s “prophecies.” In other words, since corporations in our age are just as intent on selling consumers ways of listening to music—Spotify, YouTube music—as they are on producing the music itself, recordings have really become the lingua franca of the musical economy. As such, the “statements” asserted by Monsaingeon’s videography are scarcely more than the “norm” for the twenty-first century viewer-listener.

This probably isn’t the case, however: despite the radically open-access nature of the All of Bach project, it seems that audiences are unable to move beyond the traditional expectations of the concert hall.

As Said notes in his aforementioned essay, the traditional concert pianist, via “digital wizardry,” sought to “impress and ultimately alienate the listener/spectator,” and it was Gould who first transformed mere show into “provocation, the dislocation of expectation, and the creation of new kinds of thinking.” Yet, it is clear that online audience members like Norman Astrin are not yet prepared to take part in this dialogue between equals, and insist on alienating Rondeau as an other. Even laudatory comments fail to accept equal footing with Rondeau, despite his casual dress and modest demeanor: