It was a March night in 1939 New York City. You and a group of friends decide to go out to Cafe Society, a new night club in the former speakeasy on West 4th Street. Billie Holiday, the 23 year old up-and-coming black jazz singer, is performing. She in all her melanin splendor with a single gardenia adorned on her hair, is standing on the stage of the L shaped hall, about to perform her last piece. The lights dim to darkness and a single spotlight illuminates her golden face as she begins to sing:

Southern trees bear strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Whispers quickly spread amongst the audience.”Lynching? Is this song about lynching?” someone says. The song continues and the chatter quickly dies out as every single ear and eye is on Holiday. The room is still, the air frozen.

Pastoral scene of the gallant south,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scent of magnolias, sweet and fresh,

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh.

Here is fruit for the crows to pluck,

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop,

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

After the last word, the room snaps to black. When the lights are brought back up, Holiday is gone. No one moves. Do you applaud for the “courage and intensity of the performance, stunned by the grisly poetry of the lyrics, sensing history moving through the room? Or do you shift awkwardly in your seat, shudder at the strange vibrations in the air, and think to yourself: call this entertainment?”

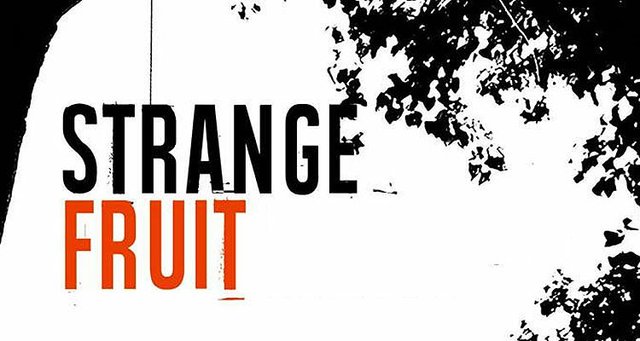

This is “Strange Fruit.” Although not written by Billie Holiday, her deeply personal and visceral vocal performance ultimately made the song an instant anthem for anti-lynching during the Civil Rights movement . The song began as just a poem written by Jewish communist Abel Meeropol, when he was inspired by this photo of a double lynching. Meerpool later composed the melody. Even though lynching was in decline at the time of piece’s composition, the image of a black person being lynched in the American south acted as a universal and incredibly vivid symbol of American racism as a whole during the Civil Rights movement, making this piece truly one of protest.

“‘Strange Fruit’ was not by any means the first protest song,” writes Dorian Lynskey for The Guardian, “but it was the first to shoulder an explicit political message into the arena of entertainment. Unlike the robust workers’ anthems of the union movement, it did not stir the blood; it chilled it.” Never before had a piece of music so explicitly called out the injustices in America by name, which is part of the reason why Holiday’s primary recording company, Columbia, refused to record the song. Holiday eventually had the piece recorded by Commodore Records, and within its first year was added to Library of Congress’ National Recording Registry.

Holiday’s piece had struck a nerve among the American people, and sent a surge forward in the progress of the Civil Rights movement. Atlantic Records founder Ahmet Ertegun called the song “a declaration of war… the beginning of the civil rights movement”. Which couldn’t be more fitting. This piece began a wave of publicizing lynchings; bringing them out of the shadows of their perpetrators and into the light–forcing the American people to face the injustice happening in their own backyards. “Strange Fruit” paved the way for future lynchings to be more publicized as a result. Take, for example, the lynching of Emmett Till in 1955 Mississippi, who at the age of 14 was lynched after being accused of offending a white women. Emmett’s body, disfigured beyond recognition when it was discovered, was displayed in an open casket funeral for all to see, so everyone will know the horrors and the aftermath of racist acts of violence.

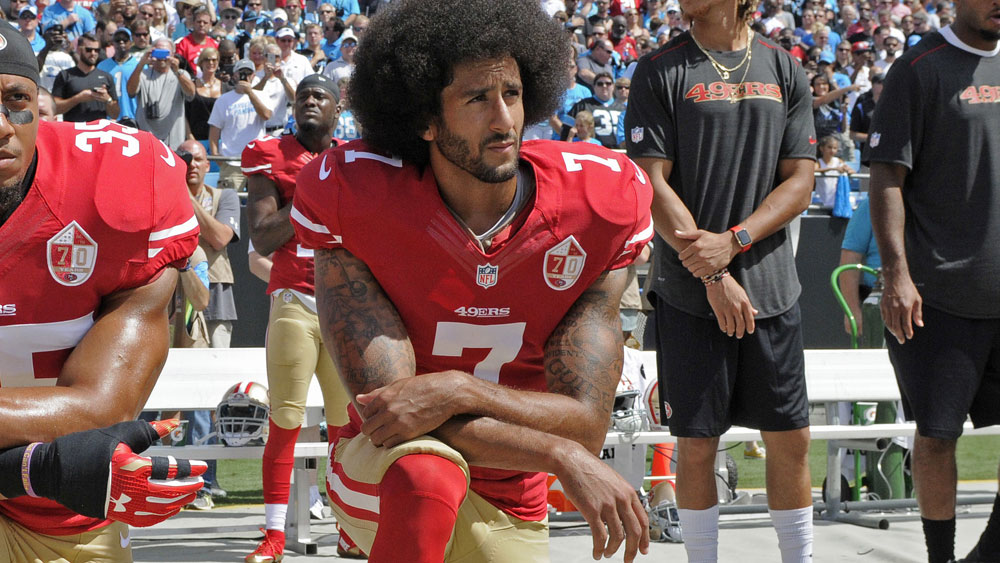

At its core, “Strange Fruit” is a song about injustice: a call to action to stop the lynchings and racist acts of violence. A call that is still incredibly necessary today, in the age of Trayvon Martin, Eric Garner, Oscar Grant, Sean Bell, and so many others. A call that has been answered boldly by the actions of some, notably San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick who refused to stand during the national anthem stating n an interview with NFL Media., “I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color…To me, this is bigger than football, and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder.”

The injustices against our black brothers and sisters, both in the murder of innocent lives and in the subtle microaggressions experienced daily by black people now in this country, can no longer be ignored a pushed aside. Which makes the message of “Strange Fruit,” as an anthem against racism of all forms, all the more relevant today. Just as the way it inspired people during the Civil Rights movement to shed light on the injustices, it inspires people in the today century to do the same. It also begs the question about the longevity of the Civil Rights movement: Did it ever really end or was it just pushed out of the forefront of the social stage to lie dormant until people were once again unable to ignore the injustices happening around them?

And what of Billie, whose voice and soul sparked a movement? Her impact as a performing artist, who seemed to sing with an “immaculate sadness,” still lives on today, even after her death. The music of Billie Holiday and the impact she had on the Civil Rights movement and their lasting effects on so many people today is undeniable. Her act of “war” really was in some ways, a bringing forth of light to show the world that racism in America was no longer something that could be covered up or hidden. Above all else, “Strange Fruit” calls for a willingness to endure–to endure through a world filled with hate until the message embedded in this song is no longer needed.

“Behind me, Billie was on her last song. I picked up the refrain, humming a few bars. Her voice sounded different to me now. Beneath the layers of hurt, beneath the ragged laughter, I heard a willingness to endure. Endure—and make music that wasn’t there before.”

Barack Obama in Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance (2007), p. 112